Betty was a hit, and the Fleischers quickly responded by featuring Betty in more films and in larger roles until finally, in 1932, she became the star of her own Betty Boop series of cartoons.

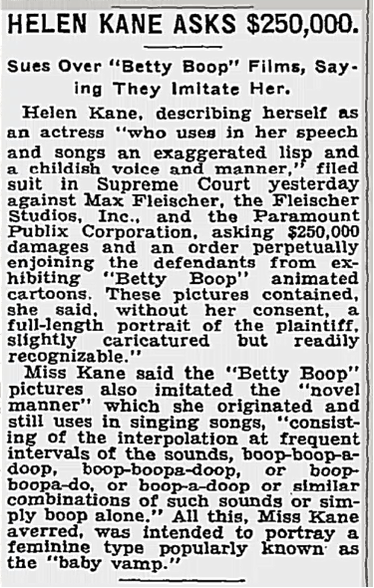

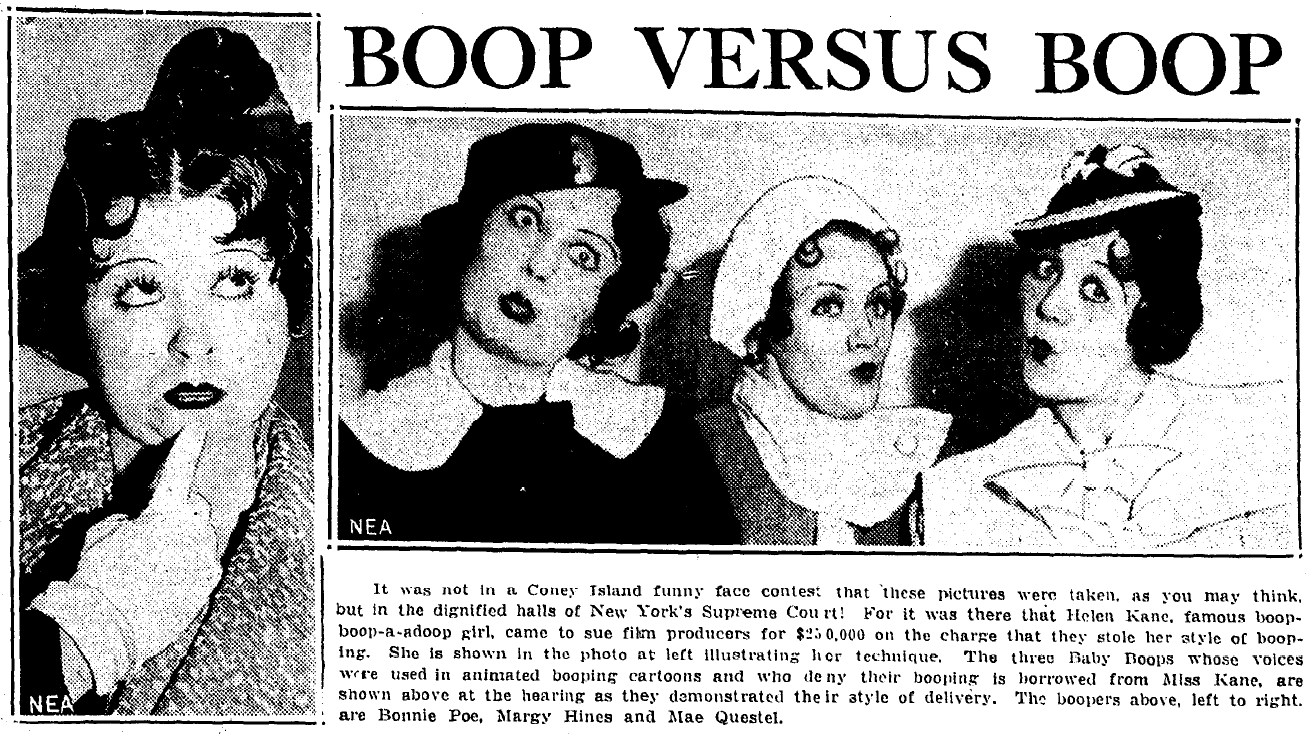

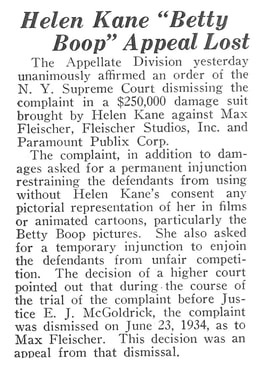

That same year, in the midst of Betty’s rising popularity, one of the well-known performers of the late 1920s, Helen Kane, filed a lawsuit against Max Fleischer and Paramount Studios, the distributor of Fleischer’s cartoons. The lawsuit, which would go on to become one of the first high-profile, celebrity lawsuits of the modern media age, claimed Betty Boop was a “deliberate caricature” of Kane and her unique “appearance, mannerisms, gesticulations, role, voice and style of singing.” Kane also claimed that, because these traits were so closely identified with her “in the public’s mind,” the character of Betty Boop constituted “unfair competition.” |

What's Scat?Scat-singing is a form of vocal improvisation common to jazz with wordless vocables, nonsense syllables or without words at all. Scat-singing gives singers the ability to sing improvised melodies and rhythms, to create the equivalent of an instrumental solo using vocal sounds, rhythms, accents and pitches.

While there are a number of theories regarding the specific foundational roots of scat-singing, it found its way into the popular music during the 1920s through the work of iconic African American performers like Joe Sims and Louis Armstrong (each of whom has been cited, at various times, as the “creator” of scat), Ella Fitzgerald, Betty Carter, Jelly Roll Morton and Cab Calloway.

LEARN MORE HERE:

|

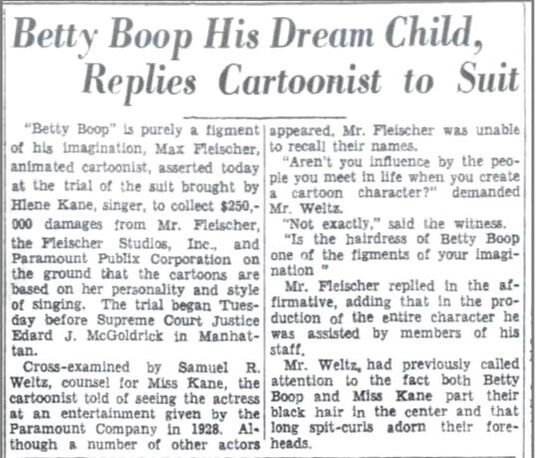

Among the characteristics Kane claimed were uniquely her own: her “baby vamp” stage personality (a seductive woman, talking in a childish voice while pouting and employing the mannerisms of a little girl); the “contour of her face and body,” which are listed in court records as “adult female, with large round baby face, pouting in baby fashion, round eyes, black curly hair, parted in the middle, curls extending away from the head and appearing on the forehead and on the side of the head, tiny nose, developed breasts, curved hips and thin ankles;” and her unique style of scat-singing.

“Scatting,” a vocal technique of inserting nonsense words or syllables into, or in place of, the traditional song lyrics or bits of dialogue, was not itself new or unique to Kane. In fact, it was already being employed with great artistry by some of the most iconic voices of the Jazz Age. But it was her particular method of scat-singing, using an exaggerated, high-pitched, childlike voice with “interpolations of the sounds Boop, Boop-a-doop and Boop-boop-a-doop,” that Kane claimed was her unique creation. Unfortunately for Kane, the practice of high-pitched scatting, along with many of the other characteristics she claimed were uniquely her own could be found in the work of several popular performers of the day. Clara Bow, Gertrude Saunders, Florence Mills, Little Ann Little, Edith Griffith, the Duncan Sisters, the Watson Sisters, and Chic Kennedy, a Broadway performer who, in 1928, claimed Helen Kane had stolen her style from Kennedy’s act, all shared several of these common characteristics and many of these performers took the stand in this hugely entertaining star-studded trial to testify for the defense on Betty’s behalf. Kane claimed her mannerisms and techniques were unique but, as was revealed during the trial, other popular artists had been using many of the same mannerisms and techniques in their own acts.

|

|

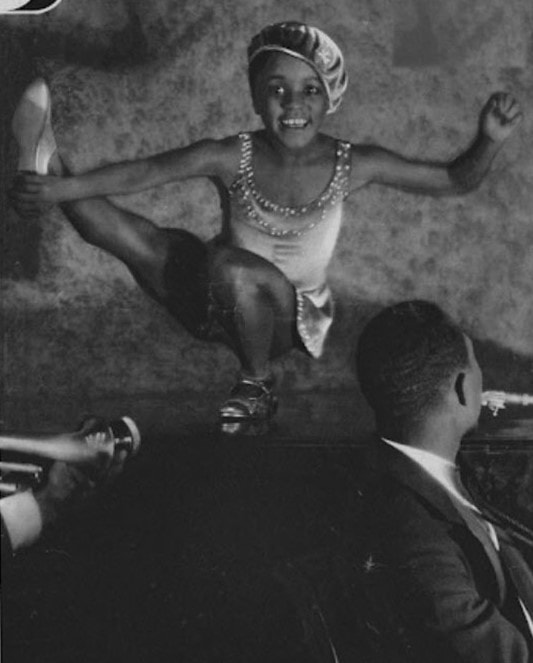

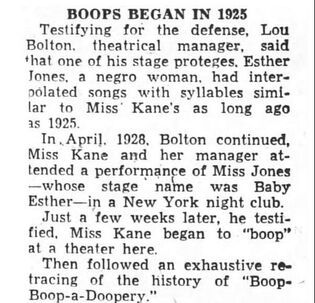

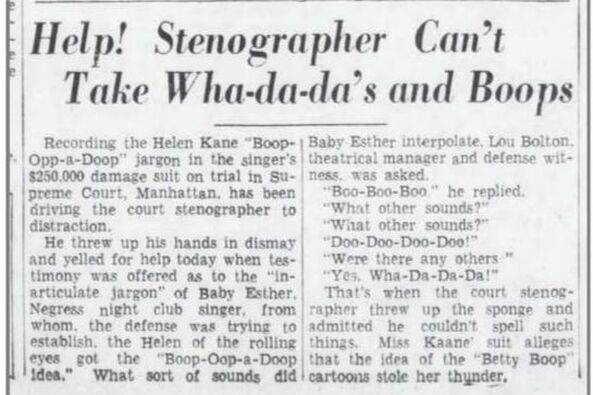

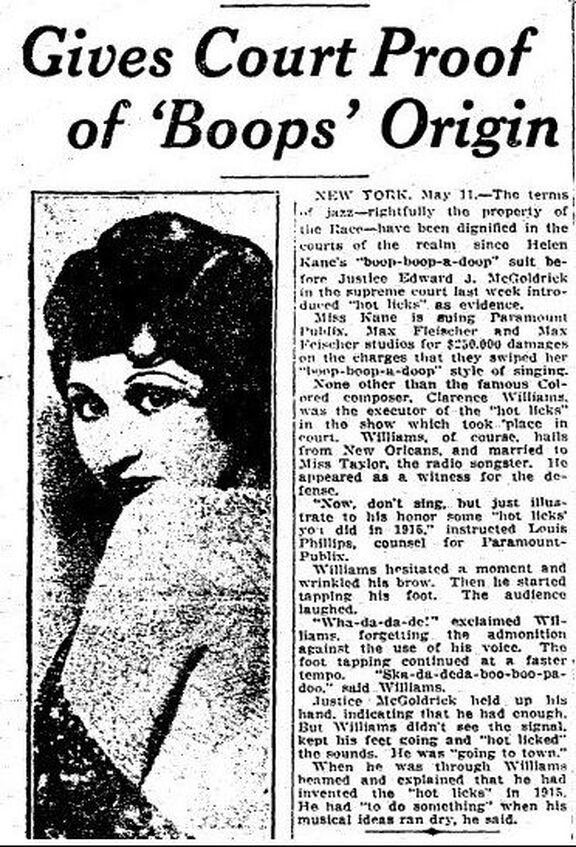

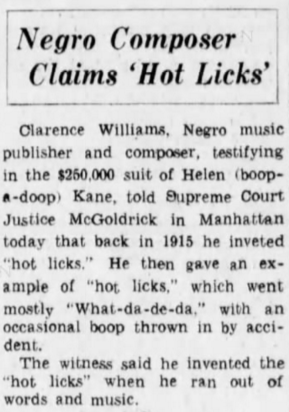

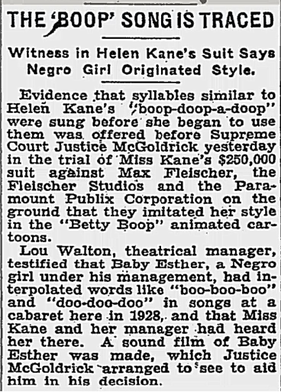

Also appearing as witnesses for the defense were recording technicians, music directors, publishers and composers, who testified that they'd witnessed other singers using the same boop-oop-a-doop style of scat-singing (at times referred to as "hot licks" or "breaks") prior to Kane's own use of the technique. Famed African American pianist, composer, performer, music producer and publisher, Clarence Williams claimed that he'd been using the technique himself since 1915; and theatrical manager Lou Bolton testified that, prior to 1928, he himself had trained an African American girl, who performed under the name Baby Esther, in the same technique of scatting using the similar phrase of “boo-doo-boo.”

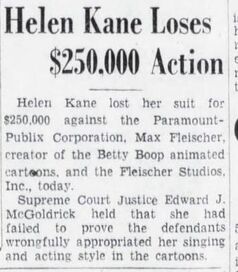

Bolton further testified that months before Kane started booping, she had seen Baby Esther perform at the Everglades Restaurant Club in Midtown Manhattan. Although Baby Esther did not appear in court herself, Bolton’s testimony was supported by an early sound film of a scat-singing Baby Esther, who was just 8-10 years old at the time and was often billed herself as a “miniature Florence Mills.” The chain of events established by Bolton's testimony, backed up by witnesses who claimed that Kane had indeed seen Baby Esther’s act, and the film evidence, established that Kane was undoubtedly well aware of the fact that she did not originate or own her “unique” singing style. The revelation created a media frenzy and was ultimately so damaging to Kane's credibility, that it is seen by many as the turning point in the case. With a steady stream of popular entertainers on the stand and court stenographers, described as being “on the verge of hysterics,” as they struggled to accurately record scat phrases from “boop-oop-a-doop” to “do-do-de-do-ho-de-wa-da-de-da,” the case captivated the public’s attention for two years and was considered to be the best show in town. Finally, on May 5, 1934, the Court ruled that, based on all the evidence presented, Helen Kane failed to show that her look, characteristics, and performing style were unique to her or that they had been taken from her by Max Fleischer to be used with Betty Boop, and denied Kane’s ownership claim of the disputed characteristics. Further, the Court did not assign these disputed characteristics to Max Fleischer, Paramount, Betty Boop or anyone else. Accordingly, the Jazz artists of the day were free to continue performing in their own personal style, many of which included the disputed characteristics of the case, while also leaving cartoon Betty free to boop her way through the 100+ animated films we continue to enjoy to this very day. Of course, during the trial Max Fleischer himself reminded the Court under oath that, unlike everyone else involved in the case, Betty Boop was after all, just a make-believe cartoon character. Max and his animators, who were based in New York City, were inspired by the talent, energy and growing diversity of the Jazz Age, and its impact on popular culture. While Betty wasn’t based on any one performer, she very clearly captured the spirit and sensibility of this remarkable and complex moment in America’s history. Today, we’re grateful for the opportunity to embrace Betty Boop’s legacy and the opportunity it offers us to celebrate and amplify the voices of so many talented, trail-blazing female performers whose influential work continues to inspire us today. |