|

Art and Technology

An interview with Ray Pointer: Part Two

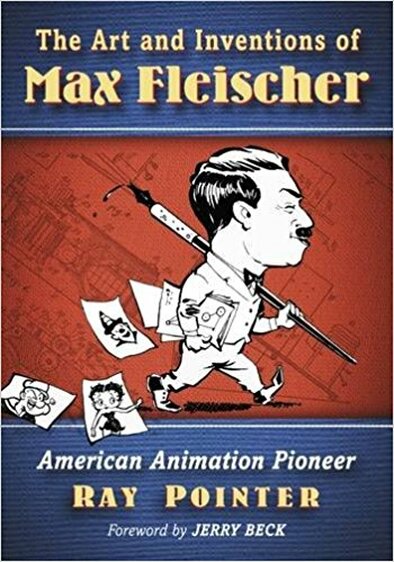

In Part One of this series of interviews Ray Pointer, animator, animation historian and author shared his early passion for the work of Fleischer Studios: how it influenced his own path as an animator and fueled the 40+-years of research that led to the publication of his recent book, The Art and Inventions of Max Fleischer.

In Part Two of this series, Mr. Pointer reflects on the marriage of art and technology that defined the old "studio system" of animation behind so many of Fleischer Studios' greatest films and most significant innovations. |

I seemed to gravitate more towards the technical aspects, and I'll admit that I neglected some of my artistic development while I focused on the details of film technology, optical sound recording, and so on which I applied to my personal films as I continued my self-training. All the same, this broad exposure to the entire process I believe has given me the depth of understanding necessary to write a book of this nature. So in order to give the subject its proper coverage, one needs to be able to "see the big picture."

|

Max talks to a reporter in BETTY BOOP'S RISE TO FAME. Max talks to a reporter in BETTY BOOP'S RISE TO FAME.

Jane: Was the Inbetween process unique to Fleischer Studios?

Ray: Some sources claim that others approached animation the same way. Winsor McCay called it a "Split System" where he made key drawings and went back and drew the in between positions. But he worked virtually alone on his animation without an assistant other than his teenage neighbor, John Fitzsimmons, who meticulously copied the backgrounds onto each drawing used in GERTIE THE DINOSAUR. Otto Messmer of Felix the Cat fame worked as an Assistant doing Inbetweens on the Charlie Chaplin cartoons. But for the most part the Inbetweening system was not in full use by other animation studios in the silent era. The story has it that it all started at Max's first studio, Inkwell Studios, when Dick Huemer left the Mutt and Jeff series and came to work for Max. Dick re-designed the clown character, named him "Ko-Ko" and had a knack for drawing directly in ink. He had a very attractive thick and thin pen line that Max liked very much. So to get Dick to work more efficiently, he asked Dick to make just the main poses and have an assistant fill in the rest of the positions. This was unheard of in those days since Animators took pride in seeing their work represented on the screen with each drawing made themselves. Art Davis was assigned as Dick Huemer's Assistant, and for all practical purposes was the first official "Inbetweener" in the business. You may recall the name Art Davis from the credits of the Warner Brothers cartoons from the 1940s on as an Animator and Director. Jane: So it sounds like the position of Inbetweener was another Max Fleischer invention. Ray: In essence, yes. It was Max's idea. And the Inbetweening method proved to be an efficient form of production, where Animators could produce more work in less time with the same results as they had when they made every drawing. This way, Animators could animate four or five cartoons in the time it would take to do one. And as animation production became more and more industrialized, this was practiced throughout the industry. But by all accounts, it started with Max's studio on the Out of the Inkwell films. Jane: This sounds like it was something of an Apprenticeship or Training Program for Animators. Ray: It was. And after some period of time, several Inbetweeners were promoted to Assistant Animators and Head Animators. And in the 1930s, Fleischer animation was largely animated on 'ones,' meaning that one drawing was made for each frame at a time when Disney cartoons were animated largely on twos, or each drawing exposed for two frames. While this cut the work in half, it did not produce the fluidity that graced the Fleischer cartoons of this period. Of course the use of animating on twos was used where smoothness of action may not have been as critical. Max made a generalized statement in the mock interview in BETTY BOOP'S RISE TO FAME where they made between 12,000 to 14,00 drawings in each cartoon.

Another form of cycle would be the musical rhythm cycle such as a character playing a musical instrument and bobbing up and down in time to the beat. The early 1930s Mickey Mouse cartoons used this a lot in their musical sequences. But this is not to be confused with the "moving hold." That was something else that Dave suggested to keep the characters alive when standing still. They would bob up and down to avoid being frozen on the screen. These were usually done randomly and not necessarily to the actual beat of the music. But the illusion was that they were moving in time with the musical tempo. That was another use of a cycle short cut.

In other cases where you had several characters working in a scene at different places on the Time Line, additional cel levels would be required, which added to the number of drawings and cel count. While there was the illusion of what in the theatrical days was referred to as "Full Animation," certain short cuts were used, similar to those used in Limited Animation for television. Fleischer Studios did have the mouth movements for dialogue in most of their cartoons on a separate level from the balance of the character. This is particularly the case in many of the Betty Boop cartoons where she sings and turns from one side to another as she sings. This is another example of a cycle. This time the mouth shapes on a top layer could be changed while the balance of the action could be cycled back and forth as needed. Even with the use of certain commercial shortcuts, there were still thousands of drawings necessary. And because of this, animation studios had to employ a large workforce to produce these many drawings within a short period of time.

|

|

Go to:

|

Ray Pointer

Ray Pointer

Ray Pointer “rolled off the Assembly Line" at Henry Ford Hospital on July 4, 1952. He attended Special Ability Art classes at The Detroit Institute of Arts, and graduated from Cass Technical High School, earning a Commercial Art degree. He attended Wayne State University and the University of Southern California, Department of Cinema/Television.

A self-taught filmmaker, Ray experimented with animation from 1963 to 1973, with his first professional exposure at The Jam Handy Organization in Detroit. And in 1973, he received the first Student Oscar for the cartoon short, Goldnavel.

Ray served in the U.S. Navy as a Motion Picture Specialist, serving in a junior officer’s position as Producer for Navy Broadcasting in Washington D.C. During this period, he received The Gold Screen Award from the National Association of Government Communicators for the animated television spots: Pride and Professionalism and Shore Patrol.

In the 1990s, Ray was active in the Animation Renaissance on the west coast, as an Assistant Animator and Storyboard Artist for Film Roman, DIC Entertainment, Hanna-Barbera, Universal, Disney Interactive, Fred Wolf Films, MGM, and Nickelodeon, where he advanced to Animation Director. In 1996, Ray became an active member of The Animation Peer Group of The Television Academy of Arts and Sciences. Since 2009, Ray has been an Adjunct Professor in Digital Media at Kendall College of Art and design in Grand Rapids, Michigan. In 2000, Ray began assembling a selection of the early Max Fleischer Out of the Inkwell and Ko-Ko Song Car-tunes films, which are available on DVD from his web site, www.inkwellimagesink.com.

A self-taught filmmaker, Ray experimented with animation from 1963 to 1973, with his first professional exposure at The Jam Handy Organization in Detroit. And in 1973, he received the first Student Oscar for the cartoon short, Goldnavel.

Ray served in the U.S. Navy as a Motion Picture Specialist, serving in a junior officer’s position as Producer for Navy Broadcasting in Washington D.C. During this period, he received The Gold Screen Award from the National Association of Government Communicators for the animated television spots: Pride and Professionalism and Shore Patrol.

In the 1990s, Ray was active in the Animation Renaissance on the west coast, as an Assistant Animator and Storyboard Artist for Film Roman, DIC Entertainment, Hanna-Barbera, Universal, Disney Interactive, Fred Wolf Films, MGM, and Nickelodeon, where he advanced to Animation Director. In 1996, Ray became an active member of The Animation Peer Group of The Television Academy of Arts and Sciences. Since 2009, Ray has been an Adjunct Professor in Digital Media at Kendall College of Art and design in Grand Rapids, Michigan. In 2000, Ray began assembling a selection of the early Max Fleischer Out of the Inkwell and Ko-Ko Song Car-tunes films, which are available on DVD from his web site, www.inkwellimagesink.com.

To learn more about Ray Pointer's search for Out of the Inkwell films - check out: