|

Surrealism

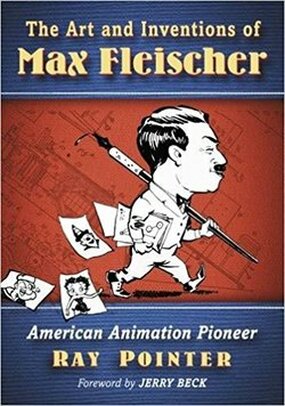

An interview with Ray Pointer: Part Four

Just in time for Halloween, the fourth and final installment of our interview with Ray Pointer, author of The Art and Inventions of Max Fleischer, focuses on the Surrealism found in so many Fleischer cartoons, and why we shouldn't let it get in the way of enjoying the opportunity to be amused.

|

|

Jane: Fleischer animation is often referred to as surreal. How did this come about?

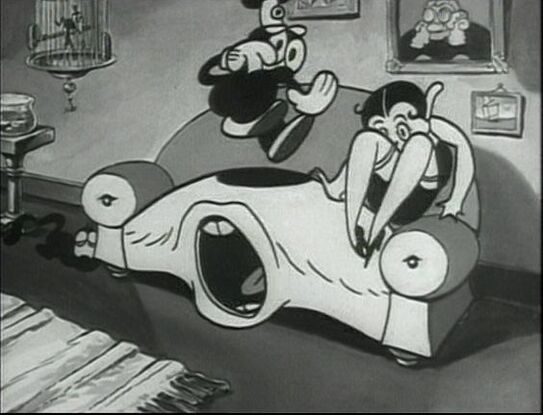

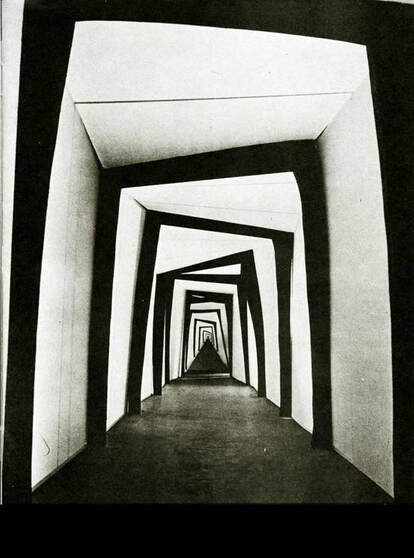

Ray: Well, first of all, that seems to be something that people have read into the cartoons in the last 30 years. What's interesting about the Surrealism that pops up in the Fleischer cartoons is the question of what should be considered the source of these elements and images. Surrealism started after World War I and continued to advance in the early 1920s. At the time it was considered "avant-garde," something practiced by artists in more intellectual circles. When you consider that the majority of the people working in the animation industry then had no education beyond high school, it's doubtful that they had much consciousness of surrealism as an art movement. Yet many surreal elements do appear in Fleischer films: the dreamlike content, the contradictions of reality. This sort of thinking was a reflection of Max's concept that, as he often stated, "If it can be done in real life, it isn't animation."

Jane: That's interesting. So would you say that Max was largely the influence in terms of the Surrealism of the Fleischer Studios cartoons?

|

|

|

The Betty Boop cartoons of the early 1930s continued the use of animating the inanimate as well. This was downplayed in the Popeye cartoons, which mostly made use of the device to symbolize Popeye's strength. In this use, it was more of a character element and clearly motivated where other uses were merely a visual gag for its own sake. This reminds me of a gag used in Ko-Ko Hot After It where Ko-Ko comes to a cliff and lassos a stump on an opposite cliff, pulling them together, and continuing on his path. This was repeated in the first Popeye cartoon with greater logic because it was in character and less of a visual gag for its own sake.

|

|

Read more of our interview with Ray Pointer

|

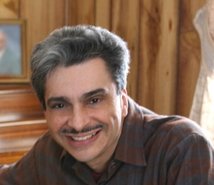

Ray Pointer

Ray Pointer

Ray Pointer “rolled off the Assembly Line" at Henry Ford Hospital on July 4, 1952. He attended Special Ability Art classes at The Detroit Institute of Arts, and graduated from Cass Technical High School, earning a Commercial Art degree. He attended Wayne State University and the University of Southern California, Department of Cinema/Television.

A self-taught filmmaker, Ray experimented with animation from 1963 to 1973, with his first professional exposure at The Jam Handy Organization in Detroit. And in 1973, he received the first Student Oscar for the cartoon short, Goldnavel.

Ray served in the U.S. Navy as a Motion Picture Specialist, serving in a junior officer’s position as Producer for Navy Broadcasting in Washington D.C. During this period, he received The Gold Screen Award from the National Association of Government Communicators for the animated television spots: Pride and Professionalism and Shore Patrol.

In the 1990s, Ray was active in the Animation Renaissance on the west coast, as an Assistant Animator and Storyboard Artist for Film Roman, DIC Entertainment, Hanna-Barbera, Universal, Disney Interactive, Fred Wolf Films, MGM, and Nickelodeon, where he advanced to Animation Director. In 1996, Ray became an active member of The Animation Peer Group of The Television Academy of Arts and Sciences. Since 2009, Ray has been an Adjunct Professor in Digital Media at Kendall College of Art and design in Grand Rapids, Michigan. In 2000, Ray began assembling a selection of the early Max Fleischer Out of the Inkwell and Ko-Ko Song Car-tunes films, which are available on DVD from his web site, www.inkwellimagesink.com.

A self-taught filmmaker, Ray experimented with animation from 1963 to 1973, with his first professional exposure at The Jam Handy Organization in Detroit. And in 1973, he received the first Student Oscar for the cartoon short, Goldnavel.

Ray served in the U.S. Navy as a Motion Picture Specialist, serving in a junior officer’s position as Producer for Navy Broadcasting in Washington D.C. During this period, he received The Gold Screen Award from the National Association of Government Communicators for the animated television spots: Pride and Professionalism and Shore Patrol.

In the 1990s, Ray was active in the Animation Renaissance on the west coast, as an Assistant Animator and Storyboard Artist for Film Roman, DIC Entertainment, Hanna-Barbera, Universal, Disney Interactive, Fred Wolf Films, MGM, and Nickelodeon, where he advanced to Animation Director. In 1996, Ray became an active member of The Animation Peer Group of The Television Academy of Arts and Sciences. Since 2009, Ray has been an Adjunct Professor in Digital Media at Kendall College of Art and design in Grand Rapids, Michigan. In 2000, Ray began assembling a selection of the early Max Fleischer Out of the Inkwell and Ko-Ko Song Car-tunes films, which are available on DVD from his web site, www.inkwellimagesink.com.

To learn more about Ray Pointer's search for Out of the Inkwell films - check out: