|

|

|

ANOTHER BOTTLE DOCTOR

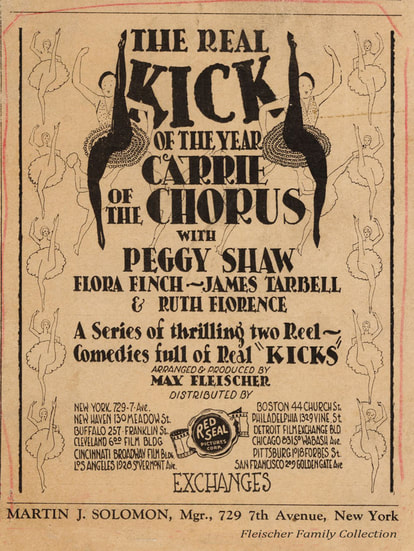

Another Bottle, Doctor may be the only surviving film from the Fleischer’s live action comedies. This silent, 24-minute-long featurette was part of their ‘Back Stage Comedy’ series, also sometimes called the ‘Carrie of the Chorus’ series.

THE PLOT: Dr. Croaker runs a quack sanitarium for an entrepreneurial undertaker. Their thriving enterprise is threatened by the arrival of a traveling medicine show selling an amazing elixir. Every male in the story falls for Peggy, a chorus girl who is part of the medicine show. Between competing for Peggy’s heart, and trying to de-bunk the elixir, all kinds of hijinks follow.

(Archival Film and Video materials from the Collections of the Library of Congress in cooperation with the National Archives of Canada Audio-Visual Section- Visual and Sound Archives.)

|

|

|