|

|

On December 6, 2015, we celebrated the 100th anniversary of the day Max Fleischer submitted a patent application to the United States Patent and Trademark Office for an invention he called the Rotoscope; an invention that would revolutionize the look of animated films…an invention that is still widely used today! On October 9, 2017, we celebrated the 100th anniversary of the date on which the United States Patent and Trademark Office officially approved Max Fleischer's patent application: October 9, 1917.

As part of this celebration we put together a compilation of vintage live action and rotoscoped footage from two early Fleischer films featuring jazz great Cab Calloway: Minnie the Moocher and Snow White. Viewing the footage from these remarkable films side-by-side reveals the level of naturalistic detail that the animators were able to achieve using the rotoscope, and the playful, imaginative and sometimes bizarre ways in which they were able to use it as the jumping off point for expressing their own vision, artistry and humor.

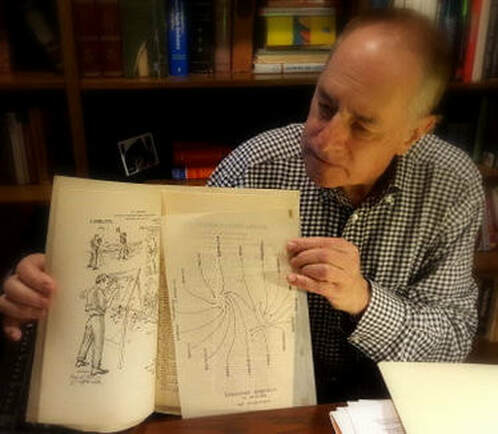

We're also pleased to share these rare photos of the original patent application (left) and the official patent document that Max received from the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office.

|

Before the Rotoscope

Max reasoned that if animators were able to use the frames of live action film as a guide, then they could create a series of drawings that, when strung together, would have a more lifelike flow. The question was how to make this logical idea into a functional and practical reality?

|

|

What one needed was a device that would enable the animator to project the film, one frame at a time, in such a way that the animator could use the image as a guide for his own work. The solution was to project the film onto the back of a small glass panel, allowing the animator to place a sheet of paper on the top side of the panel and – frame by frame - create his drawings using the projected image of motion as it unfolded frame-by-frame as his guide.

Because film during this period was shot at a rate of 16 frames per second, this would mean creating an enormous number of drawings: every single second of running time would require 16 different drawings! Once the animator had meticulously drawn all of these images, each one would have to be individually photographed so that, when strung together and projected, they would create the illusion of actual, lifelike motion. |

|

Rotoscope Patent Application by on Scribd Click on the expand icon for a full screen version of Max Fleischer's patent application. |

Max's big IdeaThe device that would make all this possible, and which would eventually become known simply as the Rotoscope, was filed with the Patent Office on December 6, 1915 under the title Method of Producing Moving-Picture Cartoons.

putting his idea into action

Max told his younger brother Dave about the Rotoscope idea. Dave, a film editor for Pathé at the time, was similarly fascinated by the idea. Together they took on the challenge of building the device that Max had imagined.

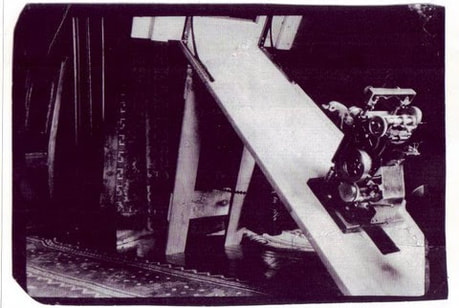

Central to the brothers’ plan was a camera, which they did not have. Fortunately, what they lacked in funding, they more than made up for with determination and innovative thinking. Thanks to their mechanical know-how and penchant for tinkering, the brothers were able to convert an old hand-cranked Moy projector (left over from a failed outdoor theater venture involving Max and his brother-in-law, Max Bertin, a year earlier) into the main component of their device. The brothers also benefitted from the talent and generosity of their other brothers: Joe, a master electrician, and Charlie, a mechanic, who both volunteered their services. Even Max’s wife, Essie, contributed to the project, offering up $150 she had managed to save from the household money.

Now all they needed was someplace to build, test and ultimately operate their Rotoscope device. They needed a space that would be large enough, cheap enough and would let them work at night – since they all had day jobs. Once again, Essie came to the rescue, agreeing to let them build their invention in the family’s living room. Making it work |

|

While the concept for the Rotoscope was relatively simple, figuring out how to make it work was anything but. Every evening for nearly a year, the brothers would meet in Max’s apartment at seven and work until three or four in the morning. The work of meticulously projecting and creating drawing after drawing after drawing was slow, tedious work.

|

|

According to Max:

It was almost a year from the time we started that we got a piece of film 100 feet long. A piece of film you could see on the screen in a minute. This represented a year’s work but it proved that the theory was correct. That one minute of film time required almost 2,500 individual drawing!

|

Back to the drawing boardWhile Max had proven his theory, he also knew that taking a year to create one minute of film wasn’t practical. The brothers went back to the drawing board, determined to create a process that was both possible and practical. Eventually, Max was able to produce about 100 feet of film every fourth week and it finally seemed as if the Rotoscope had some concrete, real-world potential.

But Max still had one hurdle left to jump, and it was a big one: he and Dave were still just two guys with day jobs, working nights in Max’s living room. Max needed to connect himself to a company that would enable him to make and, most importantly, distribute his Rotoscoped films.

Fortunately, in 1916 another early animation pioneer, J.R. Bray - who had his own studio - became interested in the Rotoscope and hired Max to join his firm. When World War I broke out, Bray sent Max to Oklahoma to create technical training films that the studio had been contracted to make for the U.S. Army. It wasn’t until Max returned to the Bray home office in 1918 that he was able to again work on films using the Rotoscope. After creating several films for Bray’s Pictograph series in 1918/19, and while still working for Bray, Max began working on his ‘Out of the Inkwell’ series. Finally, the Rotoscope was up and running!

the little clown is a big hit!The star of Max’s ‘Out of the Inkwell’ series was a character people called the ‘little clown.’ Max’s younger brother Dave, who had once worked as a clown at Coney Island’s Steeplechase Park, naturally became the clown behind the ‘Rotoscoped’ clown image. According to Max:

[I] selected the character “Koko the Clown” because he would be universally understood in pantomime. The title ‘Out of the Inkwell’ was used for want of a better name. The pictures were done in pen and ink. In addition, there are so many things that can come out of an inkwell. In the age of silent films, this rascally ‘little clown' whose antics could be easily understood and appreciated without the need for language, quickly rose to fame becoming the first of the Fleischers’ many iconic characters. A lengthy article in the New York Times (‘The Inkwell Man,” Feb. 22, 1920) describes the clown:

This little inkwell clown has attracted favorable attention because of a number of distinguishing characteristics. His motions, for one thing, are smooth and graceful. He walks, dances and leaps as a human being, as a particularly easy-limbed human being might. He does not jerk himself from one position to another, nor does he move an arm or a leg while the remainder of his body remains as if it were fixed in ink lines on paper... Dave eventually joined Max at Bray and the brothers continued to work there until 1921, when they left to form their own studio “Out of the Inkwell, Inc.” This is the studio that would eventually become known as Fleischer Studios and the place where, in 1923, the ‘little clown’ finally got his name… Koko!

|

success!Koko was an enormous success for the Fleischers, both technically and artistically. Technically, Max’s use of the Rotoscope, combined with his ingenious talent for incorporating live action film sequences into his work, created a fantastic new world in which an animated clown could ride on a live-action house cat or transport ordinary people to the furthest reaches of outer space.

It was Max himself who, more often than not, served as Koko’s foil, playing the embattled animator, the victim of Koko’s trickster pranks and the patient but stern parent who must ultimately track down his unruly ward and send him to his room, which in Koko's case was his ink well.

Far left: Dave Fleischer (left) and a cameraman, film a live action sequence to be used in the process of Rotoscoping the matching image next to it (near left), from Mr. Bug Goes to Town. The legs belong to Roberta Bottcher. Above: a short clip from Gulliver's Travels (1939) featuring the use of the Rotoscope to create Gulliver's amazingly movements. |

the rotoscope: yesterday and today |

|

While the Rotoscope is often associated with animated cartoons, over the years it's been widely used in dozens of live action films, video games, music videos and commercials. In fact, Wikipedia has compiled a lengthy (and sometimes surprising) list of Rotoscoped Works including everything from Star Wars to The Good, The Bad and the Ugly to The Bride of Frankenstein.

Today, Rotoscoping has even been adapted for computers! Although it’s applied somewhat differently, the principle is very similar to the original Fleischer invention, so much so that the process is still referred to as Rotoscoping! Computerized Rotoscoping is often used in the field of Visual Effects (VFX) to achieve the same super-realistic effect in computer animation that the Fleischers sought to achieve in early film - as can be seen in this blog post on a VFX website. |

fun fact: the challenges of working at home

|

|