|

|

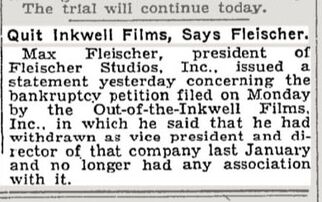

© TM & © 2023 Fleischer Studios, Inc.

Press & Media Inquiries: [email protected] Licensing & Product Inquiries: Global Icons General Information: [email protected] Terms of Use | Privacy Policy |

License Betty Boop through Global Icons, Inc.

|