|

In this installment we’ll explore Out of the Inkwell's tumultuous middle years;

from innovation and expansion... to the edge of utter collapse

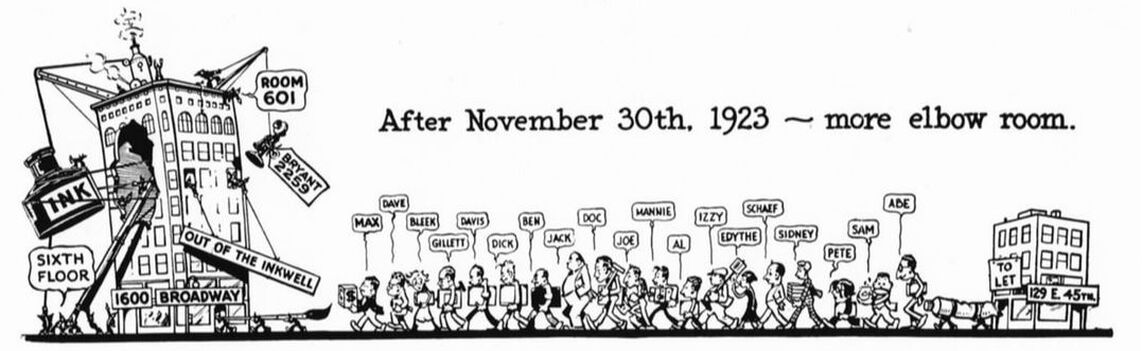

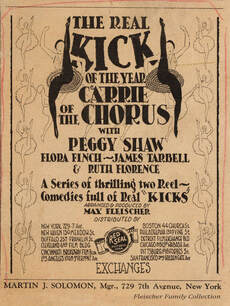

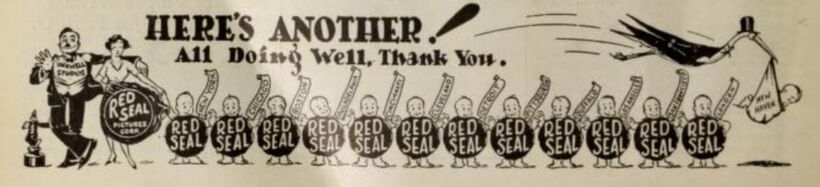

New Year, New Challenges This 1926 ad in Motion Picture World celebrates the expansion of Red Seal into new markets. This 1926 ad in Motion Picture World celebrates the expansion of Red Seal into new markets.

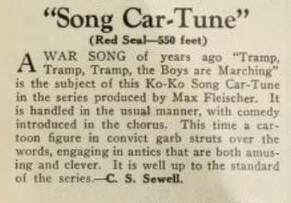

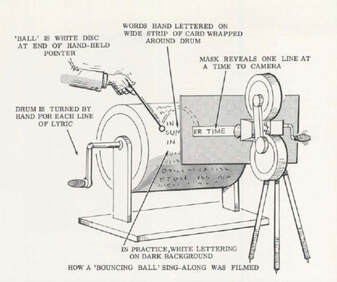

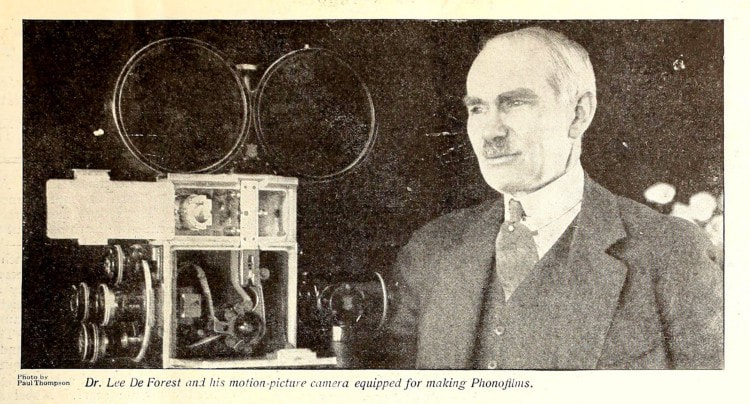

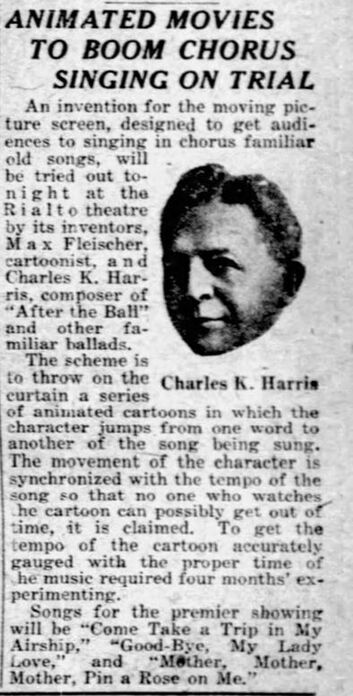

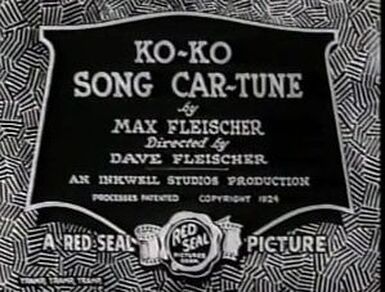

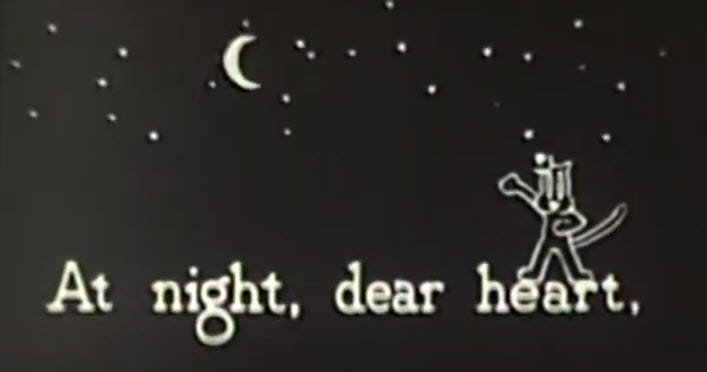

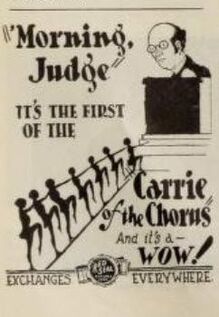

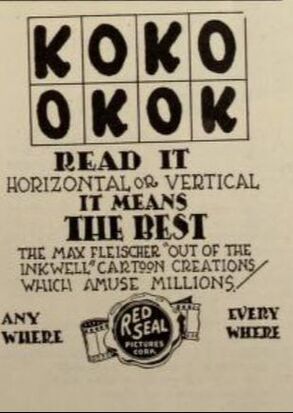

Red Seal released 26 new films in 1924 nearly all of which were animated films produced by Out of the Inkwell. These films introduced the audiences to synchronized sound, the Bouncing Ball, and production on their new Carrie of the Chorus series was well underway. It was, in short, a remarkable year for Red Seal and for Out of the Inkwell. Flush with optimism, Red Seal invested in more and more movie houses. They eventually acquired more than 50 theaters stretching as far west as Ohio and began the process of equipping the theaters with the technology they needed to present Phonofilm sound films. Red Seal also committed to releasing an astounding 141 new films in 1925.

|

|

© TM & © 2023 Fleischer Studios, Inc.

Press & Media Inquiries: [email protected] Licensing & Product Inquiries: Global Icons General Information: [email protected] Terms of Use | Privacy Policy |

License Betty Boop through Global Icons, Inc.

|